Cripple Creek, Colorado

Cripple Creek, Colorado | |

|---|---|

Entering Cripple Creek. | |

| Motto(s): "Real Fun, Real Colorado." | |

Location of the City of Cripple Creek in Teller County, Colorado | |

| Coordinates: 38°44′54″N 105°10′32″W / 38.74833°N 105.17556°W[3] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Teller County seat[2] |

| Incorporated | June 9, 1892[4] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Statutory City[1] |

| Area | |

| 3.941 km2 (1.522 sq mi) | |

| • Land | 3.941 km2 (1.522 sq mi) |

| • Water | 0.000 km2 (0.000 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,882 m (9,456 ft) |

| Population | |

| 1,155 | |

| • Density | 290/km2 (760/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 755,105 (79th) |

| • Front Range | 5,055,344 |

| Time zone | UTC−07:00 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−06:00 (MDT) |

| ZIP Code[6] | 80813 |

| Area code | 719 |

| FIPS code | 08-18530 |

| GNIS feature ID | 204769[3] |

| Website | cityofcripplecreek |

Cripple Creek is a statutory city that is the county seat of Teller County, Colorado, United States.[1] The city population was 1,155 at the 2020 United States Census.[5] Cripple Creek is a former gold mining camp located 20 miles (32 km) southwest of Colorado Springs near the base of Pikes Peak. The Cripple Creek Historic District, which received National Historic Landmark status in 1961, includes part or all of the city and the surrounding area. The city is now a part of the Colorado Springs, CO Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Front Range Urban Corridor.

History

[edit]

For many years, Cripple Creek's high valley, at an elevation of 9,494 feet (2,894 m), was considered no more important than a cattle pasture. Many prospectors avoided the area after the Mount Pisgah hoax, a mini gold rush caused by salting (adding gold to worthless rock).[7]

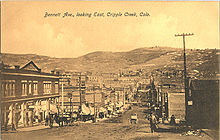

On October 20, 1890, Robert Miller "Bob" Womack discovered a rich ore and the last great Colorado gold rush began. By July 1891, a post office was established. By November, hundreds of prospectors were camping in the area. Rather than investing in mines, Denver realtors Horace Bennett and Julius Myers sought wealth by platting 80 acres of land for a townsite which they named Fremont. The town consisted of 30 platted blocks containing 766 lots. Each lot sold for $25 and $50 for corner lots. Within a year, the lots value increased and sold for at least $250 each. Months later, investors from Colorado Springs platted 140 acres near Fremont and called their town Hayden Placer. Bennett and Myers filed another plat near the Broken Box Ranch and named it Cripple Creek. The towns’ combined population totalled 600-800 people by the end of 1891. By 1892, the Cripple Creek Mining District name had caught on and in June 1892, the post office assigned the Cripple Creek name to Fremont, Hayden Placer, and Cripple Creek and all the settlements became known as one. From 1892, Bennett and Myers oversaw the Fremont Electric Light and Power Company. The district’s first telephone was established in 1893. Thousands of prospectors flocked to the district, and before long Winfield Scott Stratton located the famous Independence lode, one of the largest gold strikes in history. In three years, the population increased from five hundred to ten thousand. The Palace Hotel and the Windsor Hotel were so full that chairs were rented out to be slept on for $1 a night. Although $500 million worth of gold ore was dug from Cripple Creek and more than 30 millionaires were produced since its mining heyday, Womack was not among them. Having sold his claim for $500 and a case of whiskey, he died penniless on August 10, 1909.[8] By 1892, Cripple Creek was home to 5,000 people with another 5,000 in the nearby towns of Victor, Elton, Goldfield, Independence, Alton, and Strong. As people arrived, the marshal greeted them and confiscated their firearms, which were then sold in Denver to pay for the salary of the teachers of Cripple Creek.

In 1896, Cripple Creek suffered two disastrous fires. The first occurred on April 25 with flames resulting from a dispute between a bartender, Otto Floto, and his dancehall girlfriend, Jennie LaRue, on the second floor of the Central Dance Hall on Myers Avenue. Their struggle resulted in an oil lamp being thrown setting fire to the curtains. The fire incinerated most buildings on Myers Avenue before it was put out. Four days later, another fire destroyed much of the remaining half. A cook at the Portland Hotel spilled a kettle of grease on a hot stove, which caused fire to travel from Myers to Bennet Avenue and burned 1/3 of Cripple Creek. The town was rebuilt using brick and better construction methods in a period of a few months; most historic buildings today date back to 1896.[9]

By 1900, the Cripple Creek mining district was home to 500 mines. By 1910, it had produced 22.4 million ounces of gold. Between 1894 and 1902, around 50,000 people lived in the mining district with 35,000 in the town of Cripple Creek alone making it the fourth most populous town in Colorado at the time. The seven adjoining boom towns includes Victor, Gillette, Alban, Independence, Goldfield, Elton, and Cameron—all of which were connected by rail. During the boom, there were 150 saloons, 49 grocery stores, 25 restaurants, four department stores, 12 casinos, 34 churches, a business college, a county school district with 19 schools and 118 teachers educating almost 4,000 students, 90 doctors, 40 stockbrokers, 15 newspapers, 9 assay offices, 10 barber shops, 72 lawyers, 20 houses of ill-repute, over 300 prostitutes, 26 one room cribs, and several opium dens. Prostitution flourished until the 1920s and was taxed at a rate of $6 a month per prostitute and $16 a month per madame. Pearl De Vere, a famous madame who owned The Old Homestead, a high class brothel that serviced wealthy mine owners and entrepreneurs of the area, was known to have charged clients in the upwards of $250 a night. Over 8,000 miners worked in the district making $3 per day. Most miners and foremen supplemented their incomes by as much as 1/3 through high grading. It was estimated that an average of $1–2 million dollars per year were stolen from the early mines through high grading.

While $3 a day was typical for a miner, some miners had to work 8 hours a day while others had to work 9 or 10 hours. The average miners paid $1.75 per week for an unfurnished house or $2.50 per week to boarding houses that included a room, bath, and meals. During the 1890s, many of the miners in the Cripple Creek area joined a miners' union, the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). A significant strike took place in 1894, marking one of the few times in history that a sitting governor called out the national guard to protect miners from anti-union violence by forces under the control of the mine owners. By 1903, the allegiance of the state government had shifted, and Governor James Peabody sent the Colorado National Guard into Cripple Creek with the goal of destroying union power in the gold camps.[10] The WFM strike of 1903 and the governor's response precipitated the Colorado Labor Wars, a struggle that took many lives.

The 1904 silent film short, Tracked by Bloodhounds; or, A Lynching at Cripple Creek, directed by Harry Buckwalter, was filmed in the area.[11]

Through 2005, the Cripple Creek district produced about 23.5 million troy ounces (979 1/6 troy tons; 731 metric tons) of gold. The underground mines are mostly idle, except for a few small operations. There are significant underground deposits remaining which may become feasible to mine in the future. Large scale open pit mining and cyanide heap leach extraction of near-surface ore material, left behind by the old time miners as low grade, has taken place since 1994 east of Cripple Creek, near its sister city of Victor, Colorado. The district’s population began declining starting in 1905 as mines began closing. By 1920, only 40 mines were in business, and by 1945 the number dwindled to just 20 mines.

The current mining operation is conducted by Cripple Creek & Victor Gold Mining Company (CC&V), run currently by Newmont Mining. The mine operates 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Mine operations, maintenance, and processing departments work a rotating day/night schedule in 12-hour shifts.

With many empty storefronts and picturesque homes, Cripple Creek once drew interest as a ghost town. At one point, the population dropped to a few hundred, although Cripple Creek was never entirely deserted. In the 1970s and 1980s, travelers on photo safari might find themselves in a beautiful decaying historic town. A few restaurants and bars catered to tourists, who could pass weathered empty homes with lace curtains hanging in broken windows.

Colorado voters allowed Cripple Creek to establish legalized gambling in 1991. Cripple Creek is currently more of a gambling and tourist town than a ghost town. Casinos now occupy many historic buildings. Casino gambling has been successful in bringing revenue and vitality back into the area. It also provides funding for the State Historical Fund, administered by the Colorado Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation. In 2012, Colorado casinos produced over $104 million in tax revenue for these programs.[12][13]

Geography

[edit]The gold-bearing area of the Cripple Creek district was the core of an ancient volcano within the central Colorado volcanic field, last active over 30 million years ago during the Oligocene.[14] Free or native gold was found near the surface but at depth unoxidized gold tellurides and sulfides were found.

At the 2020 United States Census, the town had a total area of 974 acres (3.941 km2), all of it land.[5]

The community takes its name from nearby Cripple Creek.[15]

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Cripple Creek 3NNW, Colorado, 1991–2020 normals: 9235ft (2815m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 55 (13) |

56 (13) |

66 (19) |

68 (20) |

78 (26) |

87 (31) |

86 (30) |

85 (29) |

83 (28) |

74 (23) |

63 (17) |

57 (14) |

87 (31) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 49.4 (9.7) |

49.5 (9.7) |

58.7 (14.8) |

64.1 (17.8) |

71.5 (21.9) |

82.9 (28.3) |

83.7 (28.7) |

80.0 (26.7) |

77.2 (25.1) |

69.3 (20.7) |

58.7 (14.8) |

50.4 (10.2) |

82.9 (28.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 34.3 (1.3) |

36.1 (2.3) |

43.2 (6.2) |

48.9 (9.4) |

59.3 (15.2) |

71.2 (21.8) |

75.7 (24.3) |

72.3 (22.4) |

66.8 (19.3) |

54.9 (12.7) |

42.5 (5.8) |

34.3 (1.3) |

53.3 (11.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 24.3 (−4.3) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

32.1 (0.1) |

37.4 (3.0) |

46.7 (8.2) |

57.8 (14.3) |

62.3 (16.8) |

59.7 (15.4) |

54.0 (12.2) |

42.7 (5.9) |

32.7 (0.4) |

24.4 (−4.2) |

41.6 (5.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 14.4 (−9.8) |

14.6 (−9.7) |

21.0 (−6.1) |

25.9 (−3.4) |

34.1 (1.2) |

44.4 (6.9) |

48.9 (9.4) |

47.1 (8.4) |

41.1 (5.1) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

22.8 (−5.1) |

14.4 (−9.8) |

29.9 (−1.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −3.0 (−19.4) |

−4.1 (−20.1) |

3.0 (−16.1) |

9.7 (−12.4) |

18.9 (−7.3) |

33.2 (0.7) |

42.8 (6.0) |

40.5 (4.7) |

28.8 (−1.8) |

12.6 (−10.8) |

5.3 (−14.8) |

−5.9 (−21.1) |

−10.3 (−23.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −11 (−24) |

−22 (−30) |

−3 (−19) |

−3 (−19) |

8 (−13) |

26 (−3) |

38 (3) |

37 (3) |

18 (−8) |

−7 (−22) |

−14 (−26) |

−16 (−27) |

−22 (−30) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.51 (13) |

0.55 (14) |

1.31 (33) |

1.67 (42) |

1.81 (46) |

1.77 (45) |

3.20 (81) |

3.43 (87) |

1.71 (43) |

0.89 (23) |

0.57 (14) |

0.56 (14) |

17.98 (455) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 7.7 (20) |

11.3 (29) |

11.3 (29) |

14.6 (37) |

8.1 (21) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

1.5 (3.8) |

8.7 (22) |

7.1 (18) |

11.3 (29) |

82.3 (210.61) |

| Source 1: NOAA[16] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: XMACIS (2006-2020 snowfall, records & monthly max/mins)[17] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 10,147 | — | |

| 1910 | 6,206 | −38.8% | |

| 1920 | 2,325 | −62.5% | |

| 1930 | 1,427 | −38.6% | |

| 1940 | 2,358 | 65.2% | |

| 1950 | 853 | −63.8% | |

| 1960 | 614 | −28.0% | |

| 1970 | 425 | −30.8% | |

| 1980 | 655 | 54.1% | |

| 1990 | 584 | −10.8% | |

| 2000 | 1,115 | 90.9% | |

| 2010 | 1,189 | 6.6% | |

| 2020 | 1,155 | −2.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census | |||

In the early years, miners arrived without their families to seek their fortunes. Once settled, their families joined them leading the district’s population to ballon. Over 1/3 of the district’s citizens were White and Catholic. Swedes were a large enough ethnic group to have established their own newspaper, Svenska Posten. Hundreds of French people lived in the district and owned many businesses. A small population of Chinese and African Americans secured employment in the laundry business and as porters in saloons. The Chinese were not allowed to work on mines and only a handful of African Americans were hired as miners. A good mix of Irish, French, German, African Americans and Chinese women worked as prostitutes who charged between 50 cents to $1.[citation needed]

As of the census[18] of 2000, there were 1,115 people, 494 households, and 282 families residing in the city. The population density was 988.7 inhabitants per square mile (381.7/km2). There were 737 housing units at an average density of 653.5 per square mile (252.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 92.29% White, 0.90% African American, 2.15% Native American, 0.81% Asian, 1.43% from other races, and 2.42% from two or more races. 6.01% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 494 households, out of which 23.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.7% were married couples living together, 7.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 42.9% were non-families. 30.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 4.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.26 and the average family size was 2.82.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 22.2% under the age of 18, 10.4% from 18 to 24, 29.2% from 25 to 44, 30.2% from 45 to 64, and 8.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 104.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 100.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $39,261, and the median income for a family was $41,685. Males had a median income of $27,600 versus $25,000 for females. The per capita income for the city was $19,607. About 4.7% of families and 6.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 3.8% of those under age 18 and 6.1% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture

[edit]

The Cripple Creek and Victor Narrow Gauge Railroad, a narrow gauge train ride from Cripple Creek passes several small ghost towns, goldmines, and glory holes. The Mollie Kathleen Gold Mine provides tours into a real gold mine led by a real gold miner.[19]

In 2006 Cripple Creek broke ground on the new Pikes Peak Heritage Center. Constructed at a cost over $2.5 million, the building is over 11,000 square feet (1,000 m2) of educational displays. State of the art electronics are used throughout the building and there is also a theatre showing historical films about the area. Newly named the Cripple Creek Heritage Center, admission is free.

Cripple Creek is also home to the Butte Opera House, a theatre first managed by the Mackin family (previous owners of the Imperial Hotel and producers of a long-running, much-loved melodrama theatre company). The Butte is currently the home of the Mountain Rep Theatre Company that produces plays, musicals, and classic melodramas year-round, including such shows as Forever Plaid, Hot Night in the Old Town, A Cripple Creek Christmas Carol, The Rocky Horror Show, and The Christmas Donkey[20].

Cripple Creek features many events throughout the year like the Cripple Creek Ice Festival,[21] Donkey Derby Days,[22] the July 4 Celebration, the annual Ice Castles [23], and a Gold Camp Christmas.

Education

[edit]Cripple Creek is served by the Cripple Creek-Victor School District RE-1. The district has one elementary school and one junior/senior high school, including Cresson Elementary School and Cripple Creek-Victor Junior/Senior High School. Principal of the Jr/Sr High School is Daniel Cummings and Miriam Mondragon is the Superintendent of Schools.[24]

See also

[edit]- Cripple Creek and Victor Narrow Gauge Railroad

- Cripple Creek & Victor Gold Mine, active gold mine between the two towns

- Gold Belt Tour National Scenic and Historic Byway

- Pearl de Vere, known as the "soiled dove of Cripple Creek"

- Gottlieb Institute, a medical research facility in Cripple Creek

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Active Colorado Municipalities". Colorado Department of Local Affairs. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ "Colorado Counties". State of Colorado, Colorado Department of Local Affairs, Division of Local Government. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Cripple Creek, Colorado

- ^ "Colorado Municipal Incorporations". State of Colorado, Department of Personnel & Administration, Colorado State Archives. December 1, 2004. Retrieved September 2, 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Decennial Census P.L. 94-171 Redistricting Data". United States Census Bureau, United States Department of Commerce. August 12, 2021. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- ^ "ZIP Code Lookup". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original (JavaScript/HTML) on November 4, 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ Dan Plazak A Hole in the Ground with a Liar at the Top (2006) ISBN 978-0-87480-840-7 (contains a chapter on the Mt. Pisgah hoax).

- ^ Robert "Bob" Womack of Colorado Archived June 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine by Joyce and Linda Womack. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ "Cripple Creek Colorado - Worlds Greatest Gold Camp - Page 2". Archived from the original on May 23, 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2014.. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "history.com".

- ^ "Tracked by Bloodhounds; or, A Lynching at Cripple Creek (1904)". The American Film Institute. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ State Historical Fund[permanent dead link], Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, Colorado Historical Society, USA.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 19, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ William C. McIntosh; Charles E. Chapin (2004). "Geochronology of the central Colorado volcanic field" (PDF). New Mexico Bureau of Geology & Mineral Resources, Bulletin. 160: 205–238. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ Dawson, John Frank (1954). Place names in Colorado: why 700 communities were so named, 150 of Spanish or Indian origin. Denver, CO: The J. Frank Dawson Publishing Co. p. 16.

- ^ "Cripple Creek 3NNW, Colorado 1991-2020 Monthly Normals". Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- ^ "xmACIS". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Feitz, L., (1968), Cripple Creek Railroads: The Rail Systems of the Gold Camp, Little London Press, Colorado Springs, ISBN 0-936564-15-6.

- ^ "(no title)". www.mountainrep.com. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ The Cripple Creek Ice Festival returned in February 2023 after 2 years | Colorado Public Radio (cpr.org)

- ^ Donkey Derby Days 2023 in Colorado - Dates (rove.me)

- ^ Cripple Creek Ice Castles (icecastles.com/cripple-creek-colorado/)

- ^ "Cripple Creek-Victor School District". Cripple Creek-Victor School District. Archived from the original on January 22, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2016.